Blog #1 “Born of a small surprise”

2021.01.06

Category: Blog

Author: Hidemitsu Kuroki

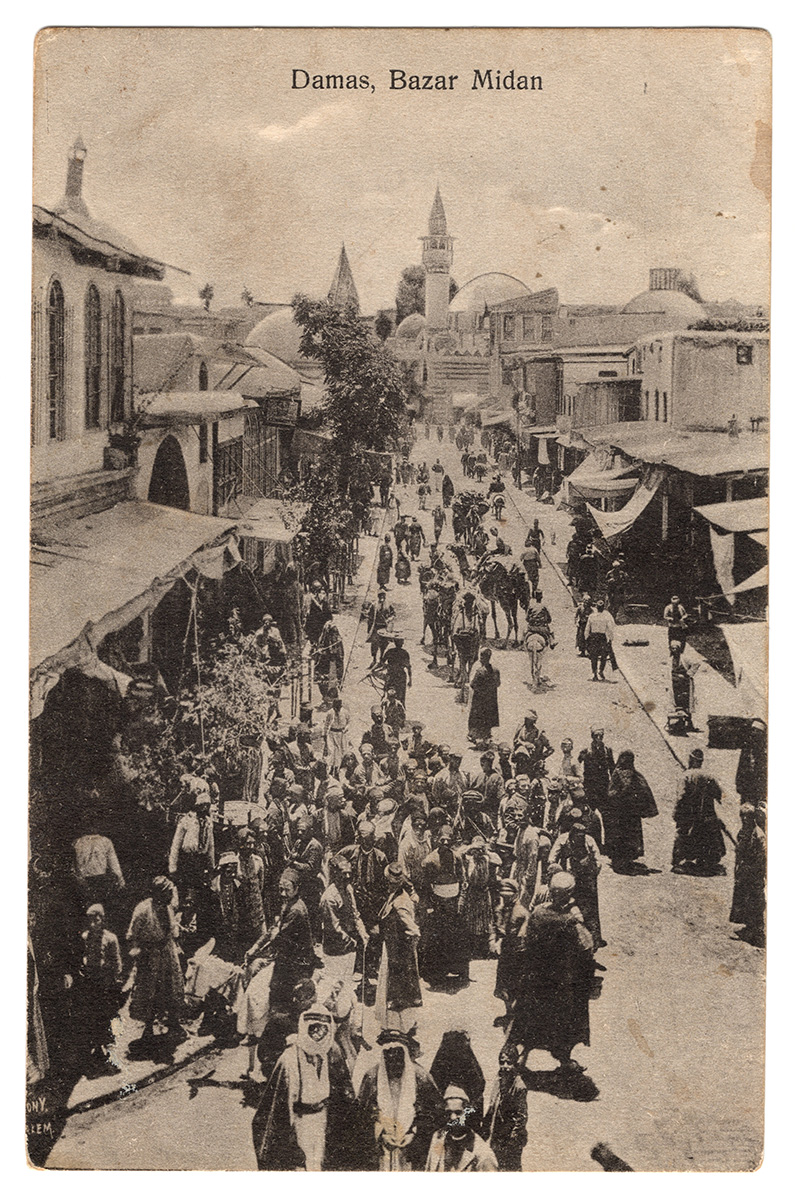

In an exclusive residential area in a suburb of Damascus, the capital of Syria, there was a large three-story apartment block with four-meter high ceilings, built mainly in the 1950s. There was a jasmine garden in the dry area of the basement unit and the autumn afternoon sun gently illuminated its rooms. It was there, nearly a quarter of a century ago, that I had just paid for a simple old Iranian Qashqai nomadic carpet. A Japanese carpet connoisseur who had introduced me to that place had told me that the large fair-skinned owner had a shop in the souk (market) in the old city that catered for tourists, but that he kept his most precious goods here. The Damascus dialect of Arabic has a soft and sweet sound like the Kyoto dialect, and this merchant spoke in the typical Damascus way.

While I was drinking one of the many cups of tea I had been offered, the assistant folded up the small carpet I had bought and put it in a bag. I stood up, shook hands with the owner, and took one last look at the pile of carpets around me. One of the carpets on top of the pile caught my eye and involuntarily I called out, “Please let me see that one.”

It was an old carpet from Kashan, a famous carpet production area in Iran. Its pattern was not flashy but well-balanced and conservative, and the red-orange base color was austere. I couldn’t move. Of all Persian carpets, Syrians, especially people from Damascus, prefer those made in Kashan. I was thus familiar with many of them, but this one looked special to me. I must have been staring at it for 20 minutes.

Finally, I asked the price. The owner said, “Generally, it costs XX dollars, but…”

After a pause of two breaths, he continued, “For you, I will sell it at YY dollars.”

As was the custom, I tried to beat him down, but he only gave me a very tiny discount. He knew that I was too taken by the carpet to haggle more aggressively.

Unfortunately though, having just bought one carpet, I did not have enough money on me. Trying to give him some notes, I said, “I’m going back to Japan tomorrow and I don’t know when I’ll be back … maybe in six months. Could you keep it for me until then? I’ll pay a deposit.”

But he just called out to his assistant and told him to fold up the carpet. A moment later the carpet was tightly folded, tied up, and put in a bag. He said to me, “Please take it.”

My mouth dropped open. “No, I don’t have enough money now. I’ll pay next time, I promise. So keep it with you.” He responded, “You can pay later. No problem. You love it, so please take it.” “But you never know what might happen. My plane might crash, or I could die in Tokyo in a car accident or from disease. It’d be a total loss for you.” “I’m happy if you’re happy. No need to give me a deposit. Just take it.”

After a long and rather strange argument, the owner gave in. I made two notes, one for the deposit and one for the balance, and handed one to him. I was relieved, but the old man seemed to have a bad taste in his mouth.

During the 1990s, I was able to stay in Damascus on several occasions for a total of three and a half years. In my dealings with the Syrians at that time, there were a few things that surprised me. The above is one of them. I don’t know if it was six months or a year later, but I was finally able to pay the balance and buy the carpet.

I could have ended this story by saying how clever the Syrian merchant was. However, in trying to finalise the transaction on the spot, this carpet seller put a certain amount of trust in me. I imagine that he thought he could take the risk since the Japanese person who introduced me was his client, so he could contact me at any time.

Why then I did not accept the carpet on the spot? I was certainly surprised by what I didn’t expect. At that time, Syria was under the dictatorship of President Hafez al-Assad (father of the incumbent president) and the Syrian economy was highly regulated in spite of its partial opening up. Essential goods and transportation were inexpensive, but Persian carpets, even though they were less expensive than in western countries and Japan, cost a huge amount. Therefore, I was totally astonished at the shop owner’s having allowed credit.

In hindsight, I can also say that I was reluctant to take on the debt, and that I was not used to such relationships and avoided them. Though there was no knowing when I would pay for the carpet, still the merchant gambled on building a relationship with me through his merchandise. However, he was finally forced to receive a deposit. He had put his trust in me and I had rejected it, reducing us to a relationship in which neither of us took any risks. That’s why he looked so sour.

A friend of mine who was doing business in Damascus told me later that traditionally Syrian merchants lent to, and borrowed from, each other on the basis of oral agreements, and that if they tried to get a letter of credit they would not be taken seriously. At the time, I was reading Islamic court documents from the nineteenth century merchant city of Aleppo in the Damascus archives, and it is true that there were occasional legal cases involving disputes over debt and credit. But my friend’s information made me realize the existence of a huge number of transactions based on mutual trust.

This project grew out of the accumulation of these small surprises. It has become clear to me that it is important for people to actively create relationships within their daily lives and to confirm with each other their “trust” in the broadest sense of the word (which includes trust in borrowing and lending).

The issues of connectivity (creating multifaceted relationships) and trust-building have been multilayered throughout the long history of Islam, from the micro level, concerning individuals, to the global level. Some of these issues have been systematized and institutionalized, while others have been hidden below the surface but remain there alive and well. It is because this awareness and idea are widely shared that fifty researchers immediately agreed to participate in this project in response to the call of the leaders of each project team.

“Mistrust” and “division” have become regularly-used words to describe the world today. In the case of Islam, this trend has become even stronger. We invite you to join us in finding and creating the knowledge that will help us overcome this. We hope that many of you will participate in our project.