Blog #17 “The Power of Words in Islamic Society: Foundations of Trust Building in Wafaa” – Part II

2023.10.18

Category: Blog

Author: Khashan Ammar

As I mentioned above, the Quran commands: “O you who believe, fulfil your obligations.” [5:1]. But it also gives more specific instructions: “Fulfil any pledge you make in God’s name and do not break oaths after you have sworn them, for you have made God your witness: God knows everything you do.” [16:91]. It goes on to say, “Honor your pledges: you will be questioned about your pledges [on the Day of Reckoning].” [17:34].

In other words, the believer who prays daily to Allah is praying in obedience to God’s promise, and the obligation to “keep one’s word” includes promises made to other human beings in the context of “obeying God’s teachings”. Which is to say, “keeping one’s word” is presented as a general obligation in all matters.

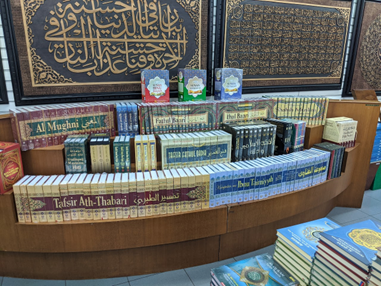

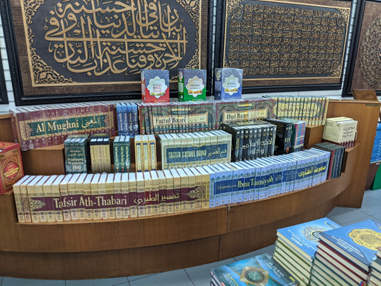

Al-Tabari (d. 923 A.D.), the Muslim scholar known for his early (and massive) exegesis of the Quran, interprets these verses dealing with promises and covenants as follows: “The commitments you make to those you battle against, the commitments you make (amid disputes) to other Muslims, the contracts between you to buy and sell [goods], to supply [drinking water], to lease [real estate or farmland], and so on. You must fulfill these contracts in good faith.”

Returning briefly to the differences between Arabic and Japanese, I was surprised to learn some of the ways in which conversations in Japanese allow for flexibility of interpretation. I refer to the Japanese terms 本音 (honne) and 建前 (tatemae). Initially, I took these words to mean “the truth” and “a lie”, both of which we have in Arabic. I was surprised to learn that honne (one’s genuine feelings and desires) and tatemae (how those feelings and desires are tempered in presentation) each have their corresponding degrees of earnestness, which can be altered to convey a particular sentiment. I was surprised to learn there exists this mutually understood means of expression wherein a commitment can be made as a formal demonstration of respect for the other party, but with a shared tacit understanding that it will not actually be carried out.

This type of contextual flexibility of interpretation doesn’t exist in Arabic. There’s not a way to say something aloud that amounts to a wafaa commitment, while simultaneously conveying the sense that the commitment is, in actuality, impractical. In Arabic and other languages of the Islamic world, what is said aloud is taken literally, otherwise it would be hypocrisy. And the act of saying it constitutes the creation of a wafaa obligation.

Photo 2: Tabari’s massive Tafsir al-Tabari (Commentary on the Quran) and other sources used in this research (photo by the author)

In this sense, the principle of wafaa is not merely moral advice or a tatemae formality. It’s core to the Islamic faith, and strongly associated with the sincerity and reliability of people making promises and verbal contracts. A person who doesn’t respect wafaa is commonly considered not a true Muslim.

There is a Hadith (a record of the words and actions of the Prophet Muhammad) that says the following regarding this point.

According to Abdullah bin Amr, the Messenger of Allah (Muhammad) said: “There are four signs that make someone a pure hypocrite and whoever has them has a characteristic of hypocrisy until he abandons it: when he speaks he lies, when he makes a covenant he is treacherous, when he makes a promise he breaks it, and when he argues he is wicked.” (Sahih al-Bukhari 34).

Thus, as a basis for trust in Islamic societies, a great importance is given to one’s word and to keeping it. I feel this is difficult to appreciate unless one presumes that spoken words are a bond. I’m currently investigating the idea that this presumption undergirds Islamic society and gives rise to mutual trust and adherence to things such as economic contracts.

As an initial underlying psychology among Muslims, wafaa (fulfillment in good faith of the obligations of a contract) shows the importance of the power of words and the faithful performance of one’s duties in local daily life and in human relations. I think this the heart of Islamic Economics and transactions in Islamic society in general. In this research project, I’m organizing these principles as expressed in the Quran and Hadith, and then analyzing them by comparing the stated opinions of interpreters, commentators, and jurists, and also experts in contemporary Islamic finance and economics. My intention is to explore specific manifestations of the principle of wafaa in Islamic society in detail, as well as how it’s applied in contemporary transactions and charitable endowment contracts.