Blog #15 “Interviews with International Migrants in Turkey”

2023.09.12

Category: Blog

Author: Sayoko Numata

“What do you want to learn? That’s what’s most important.” A second generation Tatar woman born in Japan asked me this, looking me in the eyes. It was my first visit to her house in Istanbul, Turkey. Although it was ten years ago, I remember being startled at that moment.

Turkic Muslims known as “Tatars” once lived in Japan, Manchuria, and the Korean Peninsula. They had fled their homes in the Volga-Ural region to East Asia amid the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the disorder that followed. Today, near Yoyogi-Uehara station in Tokyo, there stands a Turkish mosque known as the “Tokyo Camii.” Tatar migrants engaged in building its predecessor, the “Tokyo Mosque,” built in 1938. A school for the children of Tatar migrants was also built, a wooden building that stood until the mid-2010s.

As a researcher, I’m particularly interested in the second generation, the children of Tatar migrants, born into migrant communities in East Asia, including Tokyo, Kobe, Nagoya, Harbin, Hailar, and Keijō (present-day Seoul). By the late twentieth century, most of these first and second generation migrants had since emigrated to Turkey or the U.S.A., with the rest remaining in Japan. In other words, this was their second generation to experience intercontinental migration and relationship building. These people were born in “foreign” places (Japan, Manchuria, the Korean Peninsula) and then emigrated to other countries (Turkey, the U.S.A.), along with visits to their ancestral homeland (Russia). My aim within the Islamic Trust Studies Project is to elucidate, through narratives, the relationships between these second and third generation Tatar migrants and their host societies.

Since 2010, I’ve conducted interviews in Japan, Turkey, and the U.S.A. to learn more about the experiences of the Tatar migrants. But what kind of practice is an interview to begin with?

When we realize we want to learn more from someone whose story interests us, we begin by asking them for an interview. If the request is favourably received, we decide on a time and place, and consider various details about how the interview will proceed. We’re always thinking about the interviewee while making arrangements: Should we prepare detailed questions or let the interviewee speak as freely as possible? Should we record the conversation, take photos, or only take notes? What should we wear on the day of the interview? Is it appropriate to present a gift upon arrival?

Moreover, interviews have two participants. The interviewer asks the questions and reacts to the answers following their own interests. And the interviewee speaks in response to those questions and reactions. Conducting an interview is, therefore, interaction. In other words, the person who agreed to be interviewed also serves the role of an audience to the person conducting the interview, assessing who the interviewer is and what they hope to learn.

For each interview I conducted, I informed potential interviewees that I was a doctorate student from Japan wanting to learn the history of Tatar migrants directly from the experiences of related persons, and to publish what I learned in my doctoral thesis and books. This explanation of my intentions, however, was not necessarily enough to secure a mutual understanding between myself and the interviewee. Rather, my explanation was a starting point in building a relationship with that person.

When doing long-term research abroad, I always make it a point to acquire food, clothing, and housing locally so that I can learn something about the lifestyles of the local people while conducting my interviews. In Turkey, where I lived for four years, I had a range of different experiences, and not only during my surveys. People who participated in my surveys knew I was living with a Turkish woman in an old apartment on the European side of Istanbul. They expressed their concerns: whether I was getting enough to eat, whether I was in good physical condition, whether my housing conditions were safe and settled, whether I had sufficient income, and what I planned to do in the future. These interactions transcended the simple interviewer-interviewee relationship.

I noticed this, for example, in the way that people referred to me. Initially, they called me Japon kız (Japanese girl). But over time, some began to call me kızımız/kızım (our daughter/my daughter). This drew my attention to the norms regarding women in Turkish and Tatar migrant societies. The Turkish expression meaning “our/my daughter” is used more plainly than its equivalent in Japanese. Depending on the particular location and the flow of conversation, however, it can be necessary to act in honour of a person who has just called me their “daughter” to maintain a good relationship. Circumstances like these made me keenly aware of my being both the observer and the observed.

These are among the experiences a surveyor encounters when acquiring data (narratives) through interviews. So, my interview approach is not that of an objective and neutral observer but an active and engaged investigator of how relationships are built among second and third generation Tatar migrants. This is reflected in the second-generation Tatar woman’s question, “What do you want to learn?” My goal is to comprehend the situations of others with a depth not necessarily reflected by the act of reciting the intentions at the outset of the survey.

Book Recommendation (in Japanese)

Sakurai, Atsushi. 2012. Discussing Life Stories. Tokyo: Kobundo.

The author is the leading expert in Life Story Studies, which has developed techniques for listening to people’s narratives on-site. This book may be challenging to follow on first reading, but it offers compelling insights that will ring true after conducting interviews.

A glass of Çay I had on a ship sailing across the Bosporus on the way to an interview. (Photo by author. January 2013)

Taking tea between interview periods. The interviewee welcomed me with her carefully maintained Japan-made tea set. (Photo by author. October 2015)

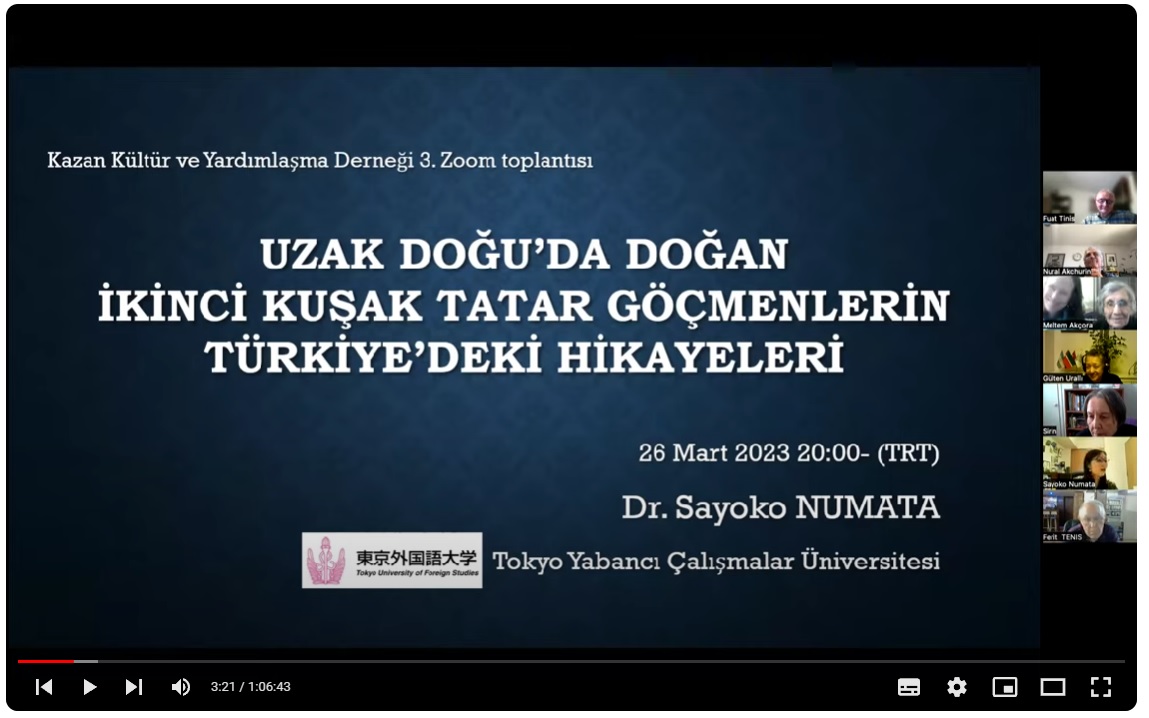

Screenshot of title card from my March 2023 online thesis presentation, held by the Kazan Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Derneği (Kazan Culture and Solidarity Association in Ankara), with participants from Turkey, the U.S.A., and Canada.

[ youtu.be/tp2D0OutKU8 ]