Blog #14 “What Are Muslims Like? — Thinking about Building Trust with Muslims”

2023.09.12

Category: Blog

Author: Sachiko Nakano

“It’s only Japanese people who always say, ‘gambaru’ (I will try my hardest)!”

These words came from an Afghan Muslim during an interview. He has been in Japan for more than 10 years, since arriving as a refugee. He knows Japanese people and culture and is fluent in Japanese with a Kansai accent.

He continued, “…there is no word equivalent to gambaru in Arabic. Instead, we have the word inshallah (if Allah wills it). Our own efforts are so small that we should believe and follow the road chosen by Allah.”

His words don’t mean that we should wait for a chance without making any effort, but mean that “we should trust in Allah and accept any outcome” after trying our best.

“Japanese tend to put both what they have done in the past and what they will do in the future down to themselves, and to force themselves into working hard, believing they need to make more of an effort. It’s a virtue, but it leaves them stressed.”

His words opened my eyes.

I was a graduate student then, and very worried that becoming a researcher might be too difficult for me, worried about my career choice, worried that I should be working harder. And exhausted by forcing myself to work even harder.

He was around my age. But he radiated inner strength, self-confidence, and emotional stability. It was so beautiful. I was jealous and amazed at a way of thinking I had never known.

His words “no need to worry about your future, because God is always watching over your efforts” lifted a burden from my heart and made me cry.

What impression do you have of Muslims?

According to a survey of 300 Japanese high school and college students, many had impressions of Muslims such as being “strict”, “serious”, “patient”, and “obviously anguished.”

The results suggest that Japanese people consider the religious disciplines of Muslims, such as fasting, worship, and restrictions on dress and diet, to be severe austerities. I also had such prejudices before starting this study.

My studies are focused on psychological analysis of how Muslims in Japan encounter Japanese people and society in the context of their faith and religious values. The hundreds of Muslims whom I interviewed and exchanged opinions with have eliminated my prejudices regarding Muslims. Their peace of mind, sympathy for others, and reliable connections fascinated me as I learned from them the strength and importance of “resolutely believing in something” (in their case, Allah).

I sometimes receive inquiries and requests from schools, local governments, and private companies for training on how to address the assimilation of Muslims. Particularly, I’m often asked what they should and should not do for Muslims. All these inquirers are quite concerned about how to avoid violating religious taboos and or causing trouble with Muslims in welcoming them.

However, there is no one perfect approach for all Muslims, as manifestations of religious faith vary from person to person. And excessive attention or assumptions such as “you are Muslim, therefore you must… (do or think such and such)” may hurt the individual’s feelings.

Surprisingly, Muslims, at least the ones I’ve met in Japan, are more flexible than people imagine.

For example, because there are few supermarkets and restaurants in Japan that provide halal food (in accordance with Muslim law), Muslims sometimes have food-related difficulties. Some of them avoid Japanese-reared meat and go to American chain restaurants. They allow themselves to eat American-reared meat because it is probably cured by Christians.

This thought is based on an interpretation that it is better to eat the meat cured by Christians or Jews, “peoples of the book”, than the meat cured by Japanese, who either don’t believe in the Abrahamic God or hold other religious beliefs. (This view is not an official interpretation of the Qur’an, but was expressed by some Muslim individuals I interviewed.)

Concerning how to deal with alcohol used for cooking and meat other than pork, the interpretations and treatments particularly vary from person to person.

Japanese society tends to treat all Muslims alike. As a result, Muslims in Japan sometimes have feelings of social pressure or fault due to excessive attention.

I wondered to what extent these difficulties were unique to Muslims in Japan. To investigate this hypothesis, in March 2023, I conducted person-to-person interviews with about 20 Muslim immigrants and refugees living in New Jersey, USA (research report forthcoming). In general, I found the Muslims in America to be less psychological conflicted. They seemed less concerned about the opinions of others, and seemed to enjoy American society’s emphasis on individuality and diversity.

I asked persons charged with assisting newly arrived refugees and immigrants to the US for tips on interfacing with Muslims. They replied, “we talk about ice cream, because when it’s hot, everyone loves ice cream!”

I was pleasantly surprised. I’d expected a staid or technical response. But they simply find something in common and enjoy it, which is the ultimate universal technique for human relationships.

As hosts, Japanese people might unconsciously frame the interactions as “what we can do for you” when dealing with non-Japanese people, who are presumed to be “different from us.”

I, however, believe the key to building trust is dialoguing on an equal footing.

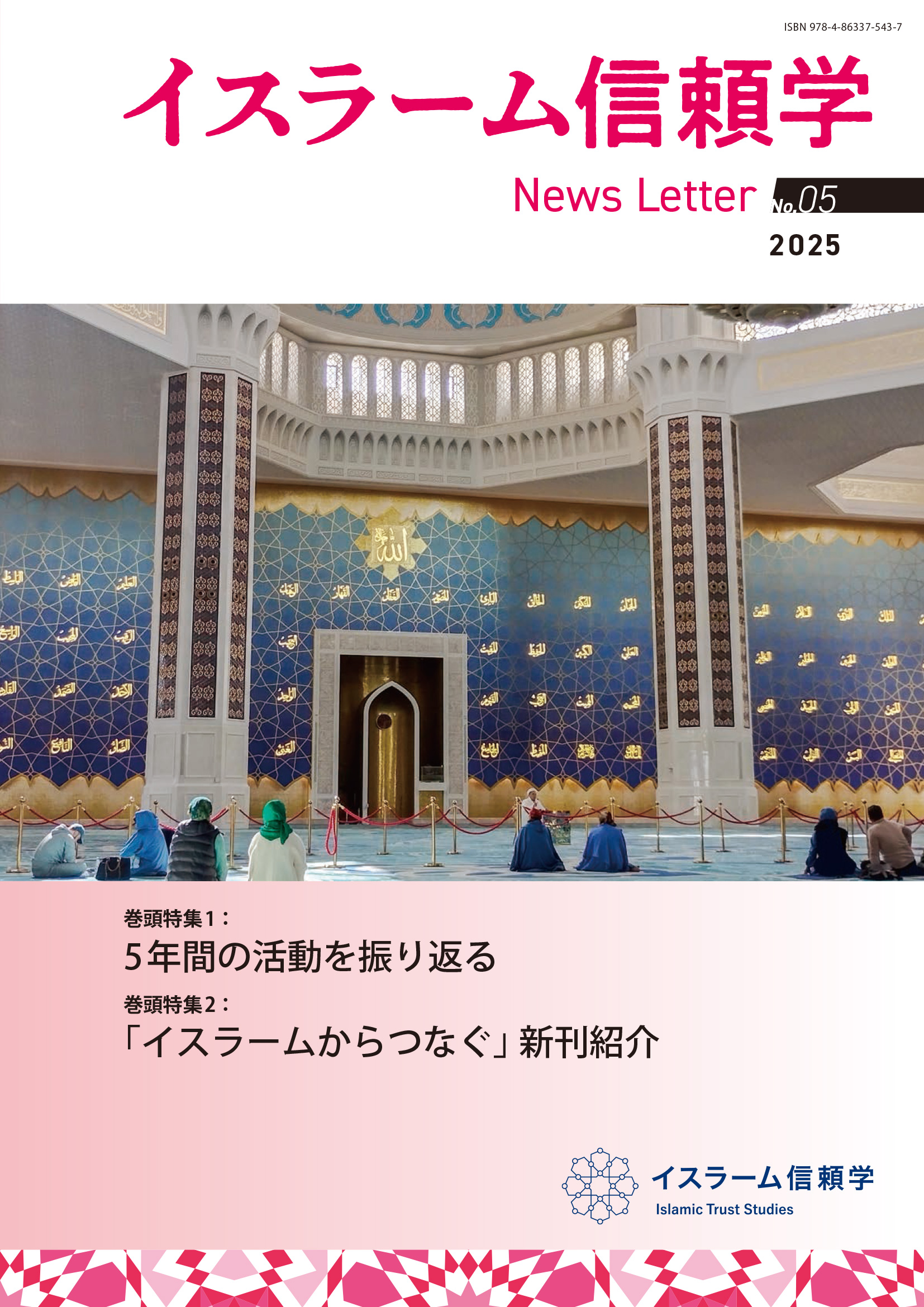

Muslim American Community Association (MACA – Voorhees Mosque) in New Jersey. This was the first post-9/11 mosque built in New Jersey. The founder was committed to building trust with non-religious people.

*All photos taken in March 2023 by the author.

The worship space inside the mosque, which also has a library, a kitchen, and a conference room.

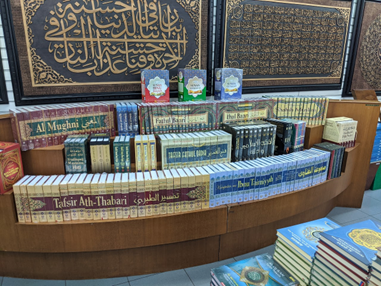

Pakistani cuisine we enjoyed in the mosque. All the dishes were quite good.

Often, my Muslim interview subjects will kindly offer me a light meal.