Blog #10 Reading Arabic-language Books on International Law

2023.01.19

Category: Blog

Author: Yutaroh OKI

I have been studying how the peoples of the Middle East and the Islamic world, particularly in the Arabic-speaking world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, acquired and applied knowledge of international law. International Law is a set of norms aimed primarily at regulating relations between nations and maintaining order in the international community. However, these late 19th century international laws were founded upon very European concepts, such as “sovereignty”, “state”, “law”, and “territory”, and organized into a customary document. In short, these were originally very Modern European ideas. So, a few regions aside, these were imported and largely unfamiliar concepts to non-Europeans. My research analyzes the earliest international legal documents written in Arabic to elucidate how these unfamiliar ideas were (or were not) accepted as international law.

For comparison, we can look at Japan during the same period. Initially, a Qing dynasty Chinese translation of American lawyer Henry Wheaton’s “Elements of International Law” (1836) was retranslated into Japanese as “Bankoku Koho [Laws of All Nations]”. Subsequent Japanese books on international law were translated directly from American and European source materials. And eventually books on the topic came to be originally written in Japanese. I’m using the phrase “books on international law” broadly here. But their composition, specific content, and even basic views on international law varied from author to author. So, through the process of publishing these books of organized principles, the Japanese translations incorporated multiple perspectives. These varying perspectives are believed to have influenced the subsequent creation of original Japanese texts and the evolution of international law in Japan.

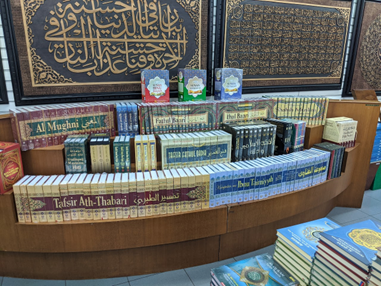

When we look into the history of books on international law written in Arabic, however, the situation is quite different. Unlike in Japan, Arabic translations of Western books are extremely rare. From the outset, these publications were original works. Close reading reveals that they did in fact reference Western books, but they’re not based on any one particular work. Multiple sources were selected from and applied. Moreover, the various Western books referenced often differed even in their basic ideas about key issues, such as what constitutes an appropriate basis for international law. In other words, multiple interpretations can be found mixed together within the same Arabic book on international law. One could critique this point as a lack theoretical consistency. But there is also something to be said for deliberately selecting from several possible sources. I am currently retracing the circumstances under which particular source books were selected, and examining the intentions and consequences of those selections.

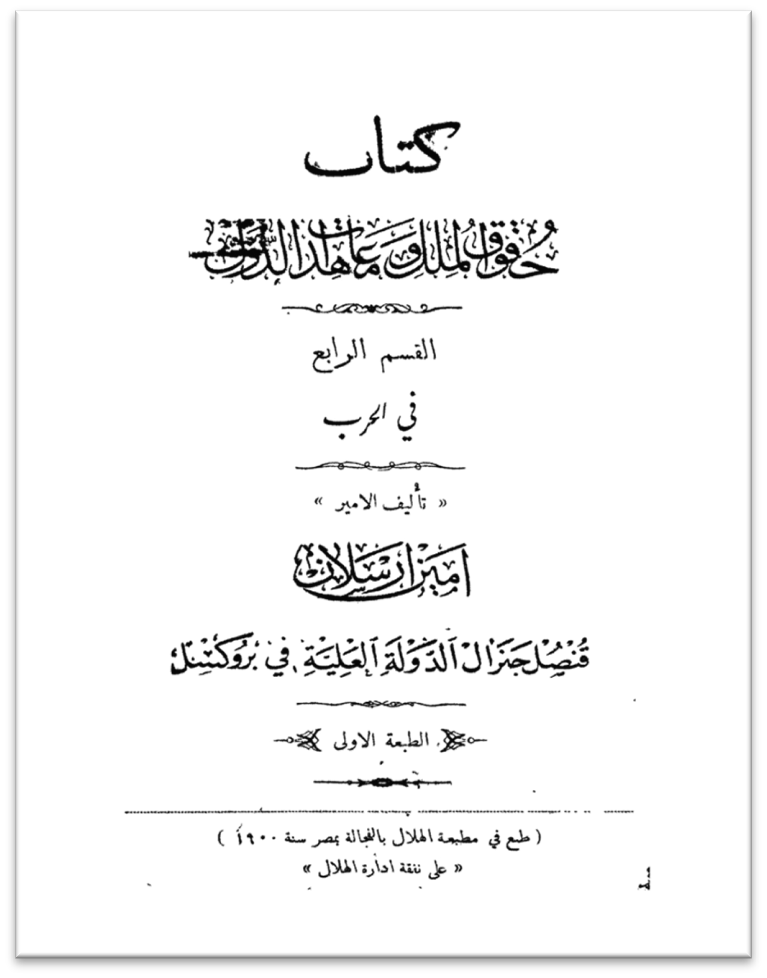

There is another particularly noteworthy feature of Arabic language books on international law. That is the diversity of connections underlying each book. For example, in 1900, an Arabic book with a title that translates to “National Rights and International Treaties” was published in Cairo. However, its author Amin Arslan was not Egyptian, but a member of a prominent Druze family in Lebanon. Moreover, the manuscript seems to have been sent from Brussels, where he was working as Consul General of the Ottoman Empire. Also, it was published by Hilal Publishing, which was founded by a Syrian-Lebanese immigrant named Jurji Zaydan. This book is not the only such example. Many of the Arabic books of that period were written, translated, or published by Syrian-Lebanese immigrants. These factors are believed to have affected the systemization and unification of Arabic terms used in translations of international law, as well as the subsequent dissemination of knowledge of international law through the Arabic-speaking world. Arabic language books on international law from this period rarely make explicit references to their predecessor Arabic books. These connections which presumably existed have been disappeared. As a future project, I see the need to assess the significance of each book through careful and empirical examination.

※The Cover of Amin Arslan’s “National Rights and International Treaties” (Cairo, Hilal Publishing, 1900)

By the way, this is a different topic, and not precisely “research”, but it is somewhat related to Islamic Trust Studies, so please hear me out. Since the Islamic Trust Studies project started in 2021, I’ve been working at the J-MENA office in the International Affairs Division of Kyushu University. This office is in charge of the Middle East and North Africa (21 countries under the MEXT’s definition of “MENA”) for the MEXT’s “Study in Japan Global Network Project”. Its main task is to promote Japanese universities to the MENA region. Our primary goal is to increase the number of talented international students in Japan. To that end, we try a number of different approaches. We establish relationships with Japanese universities interested in attracting students from MENA countries. We hold “Study-in-Japan” fairs in conjunction with these universities. We help international students create interview videos. And, to promote research and student exchanges with Japanese universities, we are building a network with MENA-country universities, high schools, related ministries, Japanese embassies, and exchange students returning from Japan. My work with local institutions has taught me a great deal about the flow of educational and academic exchange programs, both between MENA countries, and between MENA and non-MENA countries. But I still have a lot to learn. So, if you are interested in assisting me in this work, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Left: Study in Japan Fair in Amman (May 2022)

Right: Representatives of King Saud University and Japanese universities meet to discuss exchange programs (June 2022)